No further performances this season.

«Rather than doing it, try inventing it!»

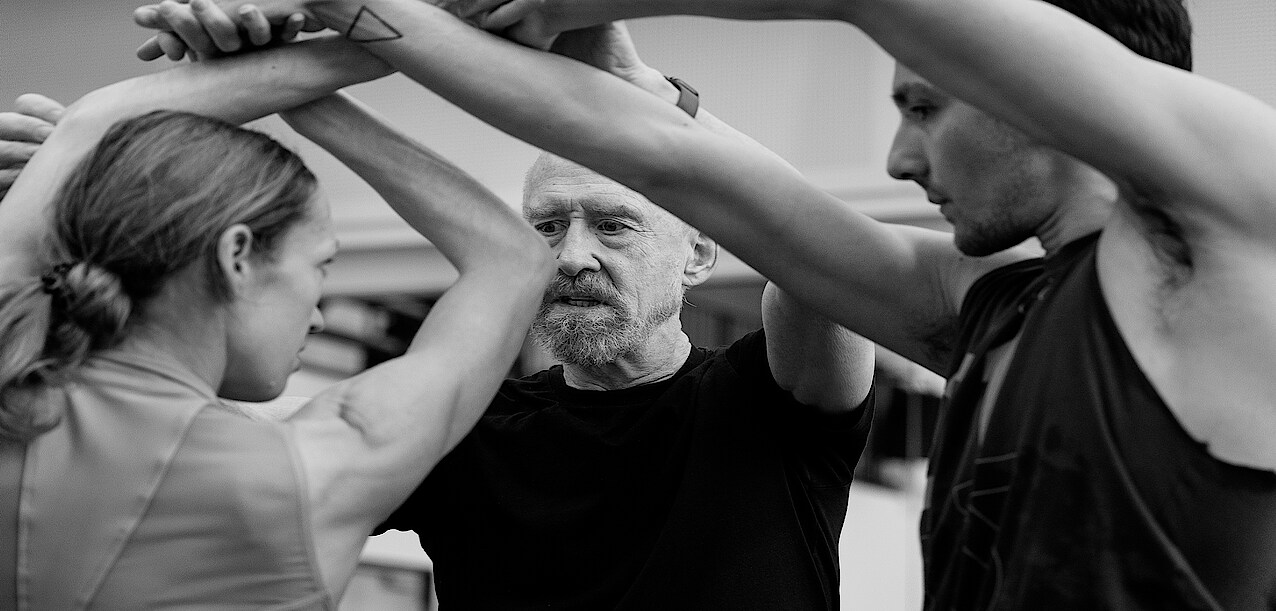

William Forsythe in conversation with Artistic Director Christian Spuck

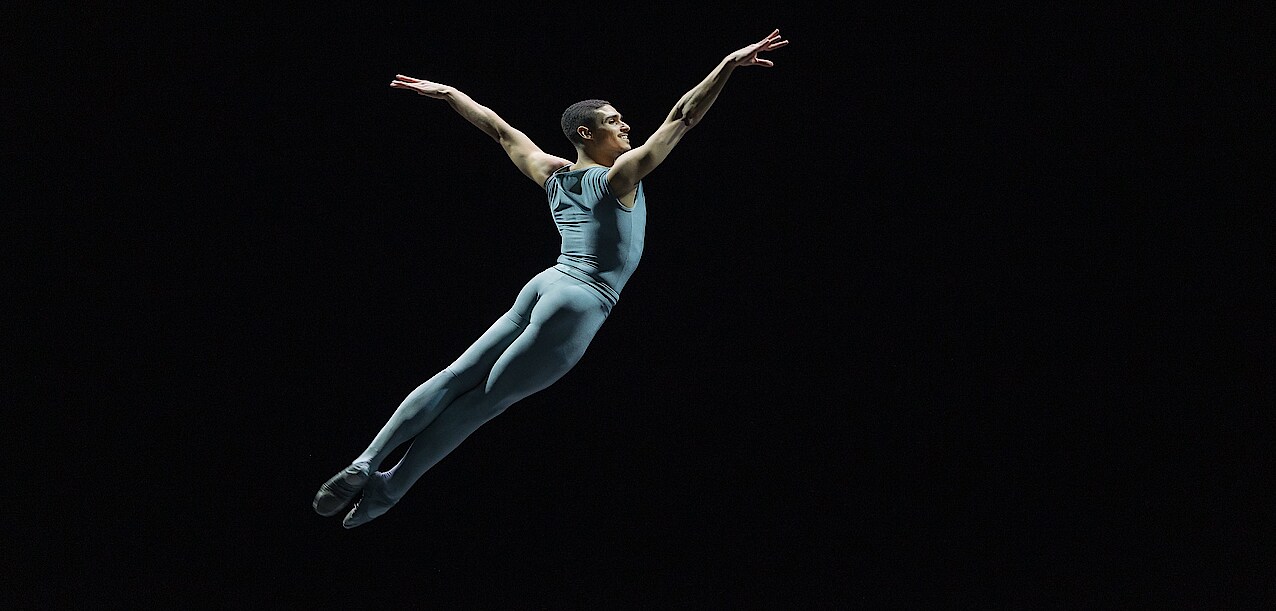

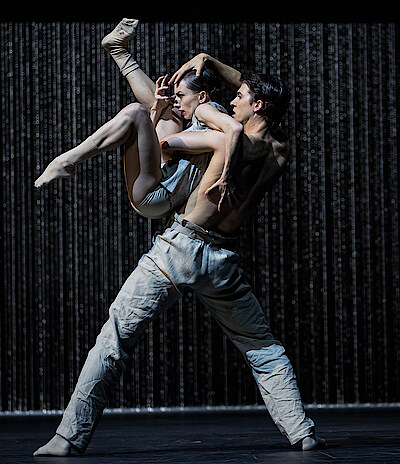

He is a legend, revered worldwide as one of the most creative and innovative renewers of the ballet tradition. In the three-part ballet evening William Forsythe, the Staatsballett Berlin dances three groundbreaking pieces by the American choreographer.

Christian Spuck (CS) I remember you telling the dancers in Zurich before their premiere, "When you go out tonight, rather than doing it, try inventing it!"

William Forsythe (WF) So, ‹doing› would imply that it's a mandatory execution. ‹Invent it› perhaps suggests something that reflects one's own perspective on the immediately available possibilities.

CS In most of your works, I see a strong influence from George Balanchine. At the same time, it's also a combination of absolutely non-classical movements and very contemporary elements. In your productions, it always seems to come from one world. How do you manage to unite these completely different worlds?

WF Virtually everything comes from ballet. One can imagine ballet as a translation process, where the dancer physically manifests their internalized model of this visual language. For them, ballet consists of ideas that feel very concrete physically. On stage, ballet cannot look like something for them, but only feel like something – a deeply ingrained state. My task is to find different ways and reasons to realize this state with them.

CS When I see your pieces, I see that you make mental processes visible on stage. How do you deal with, or how do you go about, translating such complex thought processes into dance and movement?

WF To describe one thing, I usually take a multi-layered approach with the dancers. It usually starts with proposing an idea to which the dancer gives a danced evaluation. The back and forth continues, with the dancers presenting perspectives that ultimately refine the original proposal...

CS Especially during your time in Frankfurt, I always felt a sense of premiere when I saw one of your performances. Everyone reaches their peak, and I never felt a routine. That's something very rare to find and very difficult to create. How did you manage that?

WF It's important to understand that the dancers always have a creative part in the work. I want to support that perspective. I mean, when you think about it, without them, we wouldn't have any visible ideas at all. Every dancer will have a different perspective on a role. I want them to use the working process for themselves, to promote their interests and their desire for experience in their own way.

CS You allowed yourself, for example, to change an entire pas de deux in Approximate Sonata in Zurich. So, you keep reconsidering your pieces?

WF There's the Zurich version or the Berlin version because the dancers suggest different results. They open up different paths to understand how a work functions. Ultimately, they make the history of the work, not the choreographer. In the rehearsal processes, I've come across very idiosyncratic solutions that have led ballets in very unexpected directions. I've also found that when you align your rehearsal process with the dancers' intuitive sense of possibilities for change, they can ultimately identify more with a work because it has changed through the nature of their perception. It's their version, and they made it possible!

CS So, it could be that you also develop your own version with the dancers of the Staatsballett?

WF Definitely! Each dancer has different strengths, and I adapt to them and don't insist that they do something that doesn't fit. I want to put the immense work they've already put into their abilities in the service of the matter and, based on that, find out what the work can become. I'm excited to see what can emerge! I think especially of Approximate Sonata. It's fun to work on because there are so many possibilities for variations in this piece.

CS What are the skills that a «Forsythe dancer» generally brings or must develop individually?

WF Well, that's the point: There's no «typical» Forsythe dancer. That would limit me. The unique qualities of the dancers stimulate thinking about possibilities within existing works and for future creative solutions, which I like.

CS Do you actually believe that ballet will ever become an outdated art form?

WF Ultimately, doesn't it depend on a very complex interplay of global systems? Will it not be about whether it makes economic and societal sense, or will theaters perhaps even die before ballet does? I don't know. We've already seen the migration of countless types of dance to social media, so the future of ballet might be in a different format, if at all...

Quoted from the Ballet Paper No. 2.

«As soon as I know it's impossible, I want to do it.»

Composer Thom Willems in conversation

Dutch composer Thom Willems primarily writes music for ballet and has been collaborating with choreographer William Forsythe since 1985. Together, they have created more than 65 works, including One Flat Thing, reproduced from 2016 and the 2016 Parisian version of Approximate Sonata, which is staged at the Deutsche Oper Berlin as part of the William Forsythe triple bill. In our interview, Willems discusses his music and his long-standing collaboration with Forsythe.

Staatsballett Berlin (SBB) The music for your collaborations with William Forsythe was created on the computer. How did you get involved with electronic music?

Thom Willems (TW) During my studies in The Hague with Jan Boerman and Dick Raaijmakers, who were mainly responsible for electronic music. This was actually before the beginning of electronic music, with tape loops and Moog synthesizers. The computer stuff only came at the end of the 1980s.

SBB You have been working with William Forsythe since the mid-1980s. How did the collaboration with the choreographer begin?

TW He had just started at the Nederlands Dans Theater. I was a student and saw his pieces, so I reached out to him and said, «I want to be part of what you’re doing. Let's sit down and talk.» And then we just did it.

SBB So, you've been composing for ballet ever since?

TW I just grew into it – and couldn't get out anymore. [laughs] Suddenly, I was in the ballet world, and I stayed. It was never a conscious choice. But I found the ballet world exciting and modern. I already thought classical modern music was quite dusty back then, in contrast to the ballet world, which was youthful. That suited me better.

SBB What is a typical collaboration with William Forsythe like? Do you work on a concept first, or is there a lot of improvisation?

TW We talk about ideas, but we can do that everywhere: on tour, in the studio, when we go out to eat. It's that simple. There were no real instructions, but every piece has its own conceptual demands. You work on a repertoire. What was the piece before, what came after.

SBB So, you don't necessarily have the music composed in advance?

TW There were pieces where he choreographed first, and I provided the music afterward. Or we were all together in a big studio, playing live while he rehearsed. There were many ways of collaboration. For example, during the time of The Second Detail (1991), I used to send the final version, the last mix, to the National Ballet Canada in Toronto in the evening via Lufthansa. You could simply hand the tapes to the pilot at the counter. And someone from the ballet could pick them up at the Lufthansa counter in Toronto.

SBB Nowadays, this can certainly be solved more easily with a fast internet connection. How was the music for One Flat Thing, reproduced created which premiered in 2016?

TW Everything was created on the computer. The whole piece consists of 24 tracks. I had a new plugin that allowed really good granular effects*. You could distort an existing sound file so much that it came out completely shredded. One or two sound files are oboes, but so distorted that you don't perceive them as oboes at all. When it's very deep, like a whale, that's an oboe. But that's not important. Material is material. It doesn't matter where it comes from. You try and try, and you create bad things and good things, and the good ones stay.

SBB What happens during the performance with the 24 tracks? Are there specific instructions on how to mix them, or is it all improvised?

TW The 24 tracks are like a loop, and you fade them in and out. It's a live show. Like a musician, you play the piece. For 15 years, I had always played the piece myself. It's really fun. It gives you tremendous energy. It's music that is ever-present. There are some moments in the sequence that are fixed. Otherwise, you have all the freedom to choose how to mix it. I had some performers who were supposed to play it and took it too lightly. When the performance started, they were really sweating.

SBB With 24 tracks, you can lose track easily. Do you still discover new combinations in the 24 tracks even after 15 years?

TW Yes, definitely. The variety is so vast that you can still hear new things. When Niels Mudde, who also does the sound in Berlin, rehearsed the piece and I coached him, there were results that I had never heard before. And that was very charming for me. He kept coming up with new ideas and solutions.

SBB What is the role of music in One Flat Thing, reproduced?

TW: Energy. The dancers are so full of energy, and the whole piece is bursting with energy. The music supports and directs that. And it's about tone colour.

SBB What do you mean when you talk about tone colour?

TW You should listen to Ravel's Daphnis and Chloé; that is the best music ever written. Then you understand what tone colour means. With Ravel, you can see how intelligently it's constructed because every note, every phrase gets exactly the right instrumentation. There’s nothing like it. It’s genius, it’s brilliant. Details, details, details. With the beauty of a privileged moment in time. With its radiating intelligence, this performance shows that Ravel was moving and demanding; it reveals his «L’objet juste».

SBB You also wrote the music for Approximate Sonata. How was the music for this piece created?

TW That was a bit easier. I selected from 40,000 hours of existing material. This could fit, this works or not, I listened through my own archive.

SBB What were the challenges of collaborating with William Forsythe?

TW When you collaborate with someone for 30 years, you have to constantly renew yourself. And that's the big challenge and also the big fun. Offering Forsythe an idea twice doesn't work. Even with pieces like One Flat Thing, reproduced, which are 25 years old, new ideas are still added. You have to stay attentive. That's the big adventure and journey with Forsythe.

SBB How do you search for something new? Do you have a specific method?

TW It has to do with your own repertoire. If a piece was very rhythmic, then it's certain the next piece won't be. That's how it's decided. Or if a piece has tone colour, then the next piece will be rhythmic. If a piece is overcrowded, then the next piece will be very empty. And that's how you introduce opposition into your own thinking, the search for a variety of possibilities.

Quoted from the programme brochure, 2024. The interview was conducted by Michael Hoh.

*Granular effect or granular synthesis refers to a form of sound generation in electronic music production. An existing audio file is broken down into segments, usually no longer than 50 milliseconds, called grains, and then reassembled. Similar to a film that simulates motion with 24 frames per second, granular synthesis creates a cohesive sound structure for the listener due to the short duration of audio segments.

Ballet and pop

William Forsythe choreographs to the music of James Blake

Uniting ballet and pop on stage has always been an inspiring endeavor for choreographer William Forsythe. In 1979, he choreographed his piece Love Songs, among others, to the music of Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick. Similarly, for his 1980 creation Say bye-bye, Forsythe appropriated the music of Little Richard, thus creating an eclectic amalgamation of dance and music.

James Blake's musical journey can also be described as eclectic, to whose music Forsythe choreographed one of his latest works, Blake Works I. Raised in the London suburb of Enfield, songwriter and producer Blake began classical piano lessons at the age of six. During his music studies, Singer-Songwriter Joni Mitchell was among his influences, while he also developed a fascination for the dubstep scene of the British metropolis. The genre of dubstep, inspired by drum and bass, reggae, and hip-hop, is characterized by its dark tones, complex beats, and heavy basslines. Blake significantly shaped the genre under the evolved label of Post-Dubstep. He merged the typical bass and playful beats with minimalist piano arrangements, which he always enriched with his soulful baritone voice.

He first gained recognition with his self-titled debut album James Blake in 2011 and the single «Limit to Your Love», a soulful ballad with minimally placed piano chords and reverberant beat. For the unique sonic aesthetics of his second album Overgrown, he won the prestigious Mercury Prize in 2013. In the following years, he collaborated with R&B singer Beyoncé on her album Lemonade and produced tracks on Jay-Z's 4:44 and Frank Ocean's Blonde. He won his first Grammy in 2018 for his contribution to the rap song «King’s Dead». In September 2023, Blake released his sixth studio album, Playing Robots Into Heaven.

For his work Blake Works I from 2016, William Forsythe was inspired by James Blake's third album at the time, The Colour In Anything. Forsythe selected seven songs of various styles to choreograph: from the minimalistic piano ballad «The Colour In Anything» to the synthesizer and bass drum-driven track «I Hope My Life (1-800 Mix)» to the R&B elements of «I Need A Forest Fire». This connection proves fruitful: Blake's complex soundscapes serve as a perfect backdrop for Forsythe's choreographic language of movement.

Quoted from the Ballet Paper No. 2, author: Michael Hoh