«The theatre itself can be a living Wunderkammer»

Marcos Morau in conversation

Staatsballett Berlin (SBB) Your new piece carries the German title Wunderkammer. How did the title come about, and what does it mean to you?

Marcos Morau (MM) Titles for me need to work on several levels: in sound, meaning, and the associations they evoke. Wunderkammer refers to historical cabinets of curiosities, where collectors arranged ‹exotic› objects, oddities, and bizarre artefacts that reflected a fascination with the unusual and the unknown. What interests me is that the value of these collections lay less in the objects themselves than in the stories they inspired. They combined beauty and fear, wonder and strangeness, often containing ‹monsters› – rare animals, anatomical oddities, hybrids – objects that straddled the line between nature and art, reality and imagination. Essentially, they were removed from their social context, challenging perceptions of the ‹other›.

At the same time, these collections reveal human curiosity but also hierarchies and social privilege: who could collect, who could exhibit, whose world was represented? For me, the title Wunderkammer captures this tension between fascination and power, between awe and appropriation. It’s a space for discovery and for questioning difference. In German, the word itself carries a poetic resonance, inviting the audience into an imaginative world oscillating between delight and unease.

SBB Cabinets of curiosities have a long historical tradition. How do you use them in your artistic vision?

MM History provides a framework to reflect on the present, but my aim isn’t to recreate these cabinets literally. I draw on the ideas embedded in them to make my concepts visible. I carry questions about community and individuality that I try to express. Theatre offers a space to create tension without needing to resolve it, much like a Wunderkammer that displays objects without explaining all their connections. By linking past and present, I hope to spark a dialogue in the here and now.

SBB Historical cabinets also carried colonial perspectives and claims to power. How do you explore curiosity, appropriation, and authority in your work?

MM Wunderkammern reflected both the curiosity and the power of their creators. In my piece, I explore similar contrasts. I see the theatre itself as a moving Wunderkammer – a space where the unexpected happens, ideas collide, and emotions are stirred. While historical cabinets were physical collections, my work focuses on immaterial experiences: feelings, movements, atmospheres. The stage becomes a container for various questions, just as historical cabinets held a multitude of objects, each with its own story, contributing to a broader narrative of curiosity and wonder.

SBB What are the central themes of your Wunderkammer?

MM The piece explores freedom, curiosity, and the tension between order and chaos. I want to contrast the idea of ‹beauty› with deviation and strangeness. I was inspired by the nocturnal worlds of cabaret and nightlife, places where grotesque humour, playful exaggeration, and a sense of the hidden emerged, and where rebellion could surface amid social and cultural upheaval. I wondered why Berlin, particularly during the Weimar era, saw such a proliferation of cabarets and nightclubs. These venues were diverse: alongside commercial, escapist forms, there were stages questioning societal norms, addressing political issues, and giving visibility to marginalised groups. Some offered space for experimentation and alternative lifestyles, others were primarily for entertainment. This mix reflected the ambivalence of modern city nightlife: a coexistence of innovation and conformity, artistic transgression and commercial pleasure, while the world outside was in turmoil. These places welcomed the ‹other›, yet even there the unrest of the outside world seeped in.

SBB How do you work with the dancers on a project like this?

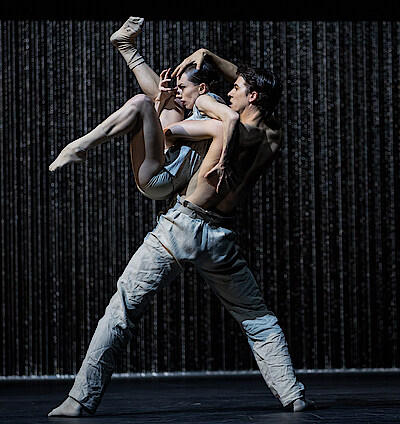

MM I like to challenge them to go beyond their usual limits. In rehearsals, they improvise, sing, speak, lead the group, and respond spontaneously. Differences and ‹mistakes› are treated as creative material. In Wunderkammer, the dancers embody the complexity of a Wunderkammer: sometimes moving in complete synchrony, sometimes performing solos or duets; some will sing, others remain silent.

SBB When it comes to interpreting your piece, how should the audience engage with it? Should they think about its historical roots or focus entirely on the present?

MM Ideally, both. I want the audience to dive straight into the performance while also sensing its deeper layers. Wunderkammer carries elements of cynicism and critique. I want to question the flow of history, the fragility of social systems we rely on, and the political and social tensions around us. Historical cabinets were places of wonder but also exclusion and assimilation. The piece explores freedom, creativity, and the search for humanity in times of upheaval. Each performance is a dialogue with the audience, inviting them to reflect on their own Wunderkammers – the inner spaces where memories, experiences, and dreams are collected – while confronting the complex contradictions of the world around us.

Taken from the programme booklet

Interview by Katja Wiegand